Justice Supreme

- Tamara Shrugged

- Oct 13, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 27, 2024

“I’d graduated from one of America’s top law schools – but racial preference had robbed my achievement of its true value. I’d been nominated to sit on the Supreme Court – but my refusal to swallow the liberal pieties that had done so much damage to blacks in America meant that I had to be destroyed.” – My Grandfather’s Son

In May of 2022, a draft opinion by Associate Justice Samuel Alito was leaked to the public, signaling the potential overturning of the longstanding legislation Roe v. Wade, a once unfathomable notion. Then, only a few weeks later, protests erupted around the country on the news of its reversal returning the matter of abortion to the jurisdiction of state legislatures. But it wasn’t Justice Alito, who provided the majority opinion, that received the bulk of the insults. Unsurprisingly, it was Justice Clarence Thomas, one of four justices to provide concurrence to the majority opinion, who provoked most of the hate. Pejoratives from Uncle Clarence, coon, and even the “n” word flowed from the mouths of progressive liberals demonizing Thomas, not only for this position but for once again refusing to bend his knee to the Democrat party mob.

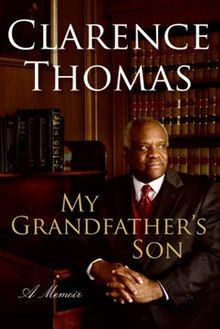

In Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas's 2007 memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son”, Justice Thomas recounts the lessons and blessings of his life that began in Georgia and ultimately led to his appointment to America’s highest court. Raised by his grandparents, Thomas shares the poverty of his youth, the struggles of his schooling, and the joys and challenges of his adulthood, in his attempt to correct the record, a record distorted by half-truths and outright lies. A descendant of slaves, Thomas’s life reaffirms that the quintessential dream of overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles, to reach the highest pinnacle of American life, is alive and well.

As a youth, Thomas navigated both his home life and Catholic rearing with structured rules and responsibilities. There would be no free rides, just hard work, backed by punishment, when necessary. Banal advice, like putting one step in front of the other, or playing the hand you are dealt prepared him for the challenges ahead. His grateful grandparents, who somehow managed to avoid the bitter resentment of racism that most couldn’t overcome, wanted only a good education and a chance for financial independence, for Thomas and his brother. All the while believing that America was the best country in the world.

Like many blacks of his age, Thomas too took a brief stint in the black power movement. He admired their “do for self” attitude, a sentiment he learned from his grandfather and would hold dear for life. But exploiting his race would come back to haunt him when affirmative action took hold and denied him of his Ivy League achievement. His Yale degree would be stigmatized, stripping him of the pride of earning it through merit when potential employers perceived it as a racial preference.

Chance meetings with black libertarians, Thomas Sowell and Walter E. Williams changed him forever, by adopting their beliefs that personal empowerment did more to help blacks than any politician ever would. But this newfound knowledge would also make him a permanent target of scorn and contempt. Like his mother and grandparents, Justice Thomas also shunned welfare, believing it was just another form of slavery, a trap that many would never escape. Instead, he believed in the redeeming power of work and saw personal responsibility as the only way out of poverty and victimhood.

Racial slurs in this youth came primarily from other blacks, while his first racial run-in with whites occurred in Boston and not the deep South, as is often the narrative. He worked to rid himself of his Georgian dialect, only to be mocked for speaking properly. He learned early that blacks were not the homogenous group many expected but exhibited the same diversity that was seen with whites who came from different backgrounds and different areas of the country. In Washington, however, he quickly discovered that if you were black, you were expected to be a Democrat. And if you weren’t, your path would not be easy. And because the government selects its apparatchiks based on party, Thomas suffered yet again. Thomas had the merit, but not the politics.

Thomas’s delight over his appointment to the Supreme Court in 1991 was short-lived when a former employee, Anita Hill, stepped forward with tales of sexual harassment during their work together. After an FBI investigation, Hill’s charges would be summarily dismissed as unsubstantiated, and Thomas’s confirmation would move forward. That is until another leak exposed Hill’s statements to the public. As Thomas soon discovered, the proverbial “man” would arrive in the form of a Democrat lynch mob, attempting to keep the wrong kind of black man down once again.

Yet, despite their numerous attempts to keep him off the court, Thomas now has the potential to be the longest-serving Supreme Court justice in history. Having maintained his strict constitutionalist views by interpreting the Constitution as written and applying it impartially based on the facts, Thomas remains a stalwart of the Founder's framework for government. The lessons from his grandfather, the virtue of personal responsibility, and the love of his country, still guide Thomas, as he sits on the summit of the American dream.

Comments